Culture

“Go back to your own country”: What a Singaporean Indian learnt during a six-month trip to India

New perspectivesThere’s possibly nothing worse you can say to an ethnic minority than “go back to your own country”, and I’ve heard my fair share. I’ve got to be honest; growing up as a dark-skinned Indian guy in Singapore has been tough. From a kid in primary school to serving National Service as a young man, people have picked on my skin colour all my life. As if that wasn’t enough, I’m dyslexic as well.

It’s that uniquely Singaporean casual racism that continues to follow me wherever I go, even in the workplace. For example, when I was mending the Japanese counter at one of Singapore’s world-class attractions, the chef remarked in front of everyone in the kitchen that he was surprised to find an Indian handling Japanese cuisine because “they can only do prata”. Sure, there might have been other occasions where jokes were made at my expense, but after some time it just gets a little boring and I can’t laugh at myself any longer.

In 2015, as I was travelling the world, one question kept popping up repeatedly: “Are you from India?” The truth is, until that point, I hadn’t even stepped foot in the country. It became important that I head there to meet people of my colour and ethnicity, as well as check out their way of life. I first visited Tirunelveli in South India, where my great grandparents were brought up, and then made my way to an experimental township named Auroville that’s known for its golden globe, Matrimandir (pictured below).

Blending in wasn’t as easy as you might think.

My initial impression of India wasn’t any different from what we see in Kollywood films: a chaotic city with jam-packed buses, sandy roads, and chai hole-in-the-walls serving milky rich masala tea. Looking at my shaggy hair, thick beard and smart shirt-and-pants outfit, the locals were curious about who I was and where I had come from. On the second day, in an effort to assimilate, I wore a short-sleeved shirt and sarong. I headed to the local chai store and attempted to imitate the local slang, instead of speaking like a Singaporean.

It worked to a certain extent, but the idea that I was coming from a different country was still very much obvious to them, even though I was of the same ethnicity, because the village was very tight-knit and everyone knew each other. Some of them even thought I was a guru and sought my blessings, solely based on my long hair and beard. After they found out I was from Singapore, they were puzzled that I didn’t appear more “modern”, clean-shaven or Chinese, which didn’t make much sense.

What I did appreciate, though, was their level of emotional vulnerability and expressiveness. They were open and willing to share their stories, often breaking down into tears or belly-laughing while talking to me.

I experienced a few culture shocks.

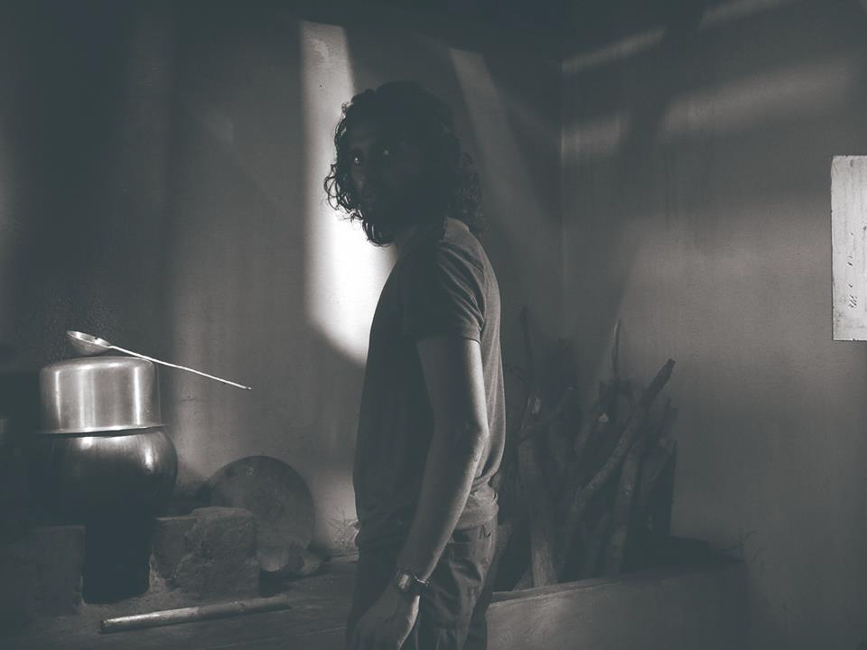

I left Tirunelveli after two months and headed to Auroville for next four months. When I arrived in Auroville, I got in touch with a chef who was running a local community kitchen (pictured below). I told her that I would love to volunteer and help her team make vegetarian food for Aurovillians.

When I began volunteering, I was surprised to encounter my first culture shock in India. In Singapore, we have been somehow taught to believe that our multiculturism is special and that it only exists within our country. However, in Auroville, I was working and living alongside a far more diverse group of people than I’ve ever encountered. They hailed from all corners of the world: Europeans from France and Denmark, Africans, as well as Koreans and Japanese folk.

On the other hand, there was one particularly distasteful incident that caught me off guard. While I was volunteering at the kitchen, a customer — who happened to be a local South Indian woman — approached me and commented that my face was just as black as my apron and kitchen uniform. It was a shock to me. I had come to expect statements like these to be made in Singapore, but definitely not in India. I remember wondering if there’s truly a place in the world, where people would be more sensitive towards my skin colour and ethnicity.

Final thoughts

Just because I looked like them, and was part of an ethnic majority, life wasn’t any easier in India. Foreigners regarded me as a local person, while locals viewed me as an outsider. That confusing perception definitely improved the longer I stayed there and interacted with them. Just like all other relationships in life, it required some time to develop. However, it was never truly resolved and I remained in a limbo as so much of my identity as an Indian is tied to being Singaporean. In either place, I exist in this state of nowhere, where I’m neither a local or a foreigner. What I learnt from my experience in India is that I should stop looking for validation from the majority, whoever and wherever that may be.

I will be returning to India this August for the first time since 2015 as part of a culinary mission with some Singaporean chefs. I’ll be in different parts of the country, so it’ll be a great opportunity to exchange and discuss not just South Asian cuisine and cooking techniques, but also celebrate our cultural similarities and traditions. I just won’t be wearing a sarong this time.

In the future, if I ever hear someone say that I should go back to my own country, I would choose to remain silent. I believe that I don’t have to prove my identity and citizenship to anyone. I wish that people would grow up and realise that this world that they live in isn’t theirs to claim. It’s temporary. We were colonised by the British and invaded by the Japanese. A civil or natural disaster could even displace us and prompt a wave of migration similar to what’s happening in other parts of the world right now. When it comes to migration, we only need to look towards the animal kingdom for many beautiful examples of being harmonious with one another as well as with the land we inhabit. I can only hope that we can work together just as pleasantly.

Kesavan Kunasegaran is a chef, community organiser, and avid traveller. He has catalysed urban and rural communities in countries such as India, Denmark, China, Japan, South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand using food and horticulture as his mediums. In 2017, he co-founded independent curatorial practice Neighborhood to create new narrative experiences and events of public value. This August, he will be travelling to India as part of a culinary mission to promote and enhance Singapore’s unique Indian cuisine.